In this post I explore two questions relating to David Chapman’s idea of nebulosity. The questions are:

- Why is zooming in relevant?

- What would a non-nebulous world look like?

Why is zooming in relevant?

David Chapman claims that the nebulosity of objects is apparent when you look really closely at them. For example:

From a distance, clouds can look solid; close-up they are mere fog, which can even be so thin it becomes invisible when you enter it.

In his other post objects, objectively, he quotes Richard Feynman:

What is an object? Philosophers are always saying, “Well, just take a chair for example.” The moment they say that, you know that they do not know what they are talking about any more. The atoms are evaporating from it from time to time—not many atoms, but a few—dirt falls on it and gets dissolved in the paint; so to define a chair precisely, to say exactly which atoms are chair, and which atoms are air, or which atoms are dirt, or which atoms are paint that belongs to the chair is impossible. So the mass of a chair can be defined only approximately.

There are not any single, left-alone objects in the world. If we are not too precise we may idealize the chair as a definite thing. One may prefer a mathematical definition; but mathematical definitions can never work in the real world.

As it is with clouds, so it is with chairs: look closely, and you realize the boundaries are ill-defined.

But this may lead us to ask: why are we “zooming in” in the first place? We seem to be assuming that a “zoomed in” view of clouds or chairs gives us a more privileged or truer picture of the chair or cloud. David Deutsch warns us against privileging the “lower layers” of abstraction over the “higher” layers when he makes his case against reductionism:

There is no reason to regard high-level theories as in any way ‘second-class citizens’. Our theories of subatomic physics, and even of quantum theory or relativity, are in no way privileged relative to theories about emergent properties. None of these areas of knowledge can possibly subsume all the others. (Fabric of Reality, chapter 1)

And he writes later (emphasis mine):

The truly privileged theories are not the ones referring to any particular scale of size or complexity, nor the ones situated at any particular level of the predictive hierarchy – but the ones that contain the deepest explanations. The fabric of reality does not consist only of reductionist ingredients like space, time and subatomic particles, but also of life, thought, computation and the other things to which those explanations refer. What makes a theory more fundamental, and less derivative, is not its closeness to the supposed predictive base of physics, but its closeness to our deepest explanatory theories. (Fabric of Reality, chapter 1)

At first glance this might make us question the validity of “zooming in” to get a “clearer picture” of a cloud, but it does not. Zooming in does give us a “truer” picture of the boundaries of the cloud or chair for the simple reason that it gives us a higher density of information about the object. This is what happens when you “zoom in” on an image, or look closely at an object with a microscope. There is actually some privilege to the “smaller scales” of reality because we’re getting a greater quantity of information per unit area/volume than we had before. If we add up all our “zoomed in” slices together, the “total information” is much greater than what we had gleaned just from looking at it from afar.

So when we “zoom in” to the cloud or chair, we get more information about those objects, and this allows us to assert that, indeed, the boundaries of the cloud and chair are ill-defined. 1

What would a non-nebulous world look like?

So, we find that when we zoom into any object in our world, its boundaries are fuzzy. But what would the world look like if the boundaries of objects were not fuzzy?

What I imagine would happen is that as you zoom closer and closer into the boundary of an object, it would remain perfectly sharp. For illustration, let’s imagine we have this potato lol:

Now imagine we zoom in on the top right edge of it:

No surprises so far. In a nebulous world, if you zoom in far enough, the edge of the potato starts looking like this:

Whereas in an non-nebulous world, it would keep looking like:

And in a non-nebulous world, if we zoomed in another 1,000,000x we would still see:

In other words, the boundary of the potato would remain perfectly sharp, perfectly crisp. It would have an “infinite self-similarity” no matter how closely you zoom in. The world would be an SVG.2

A bit of nuance on the zooming in part

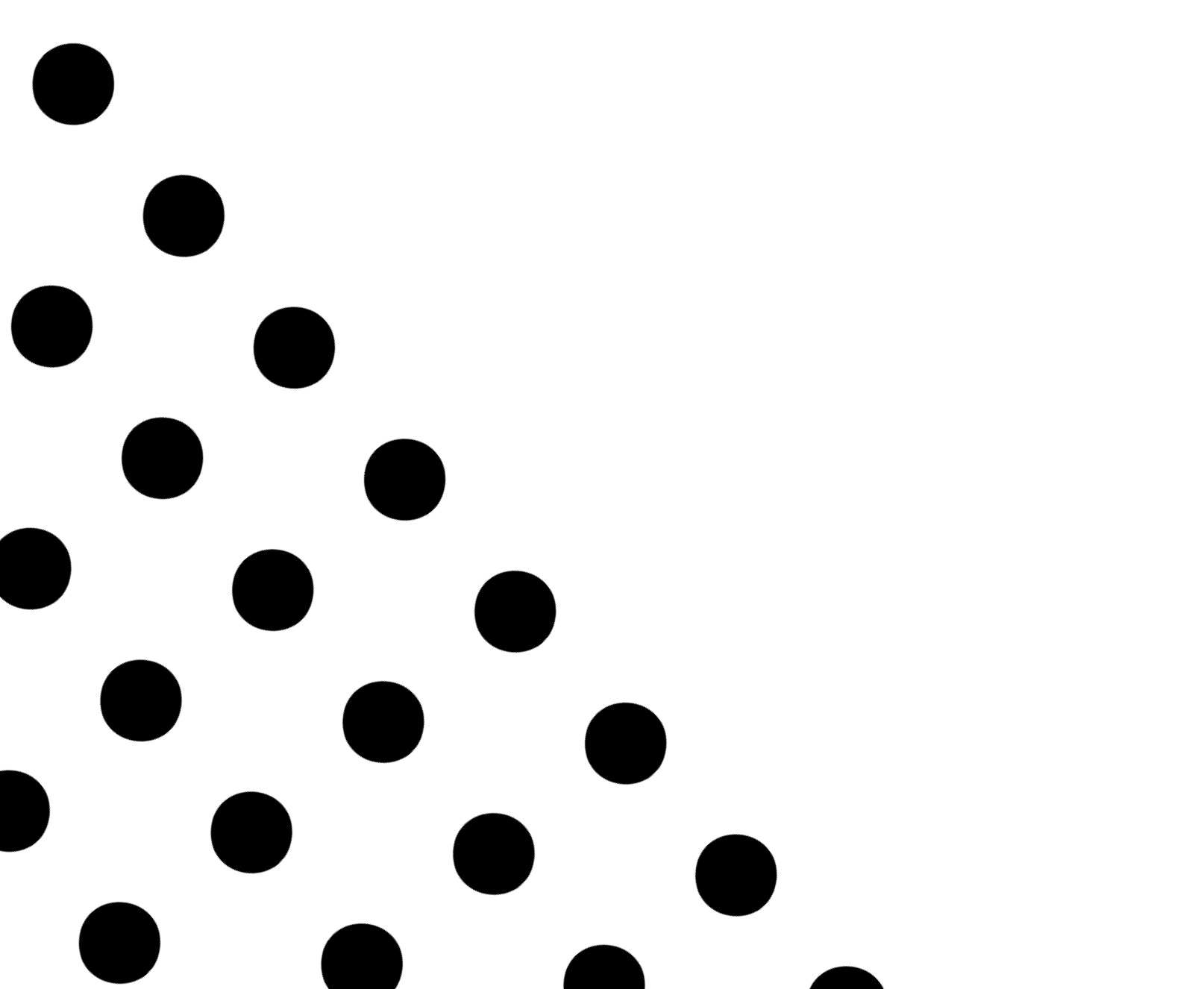

There’s a bit of nuance to add to this SVG idea that is worth mentioning. Imagine we live in a world of perfectly sharp boundaries. That need not necessarily mean that zooming into any one line will continue to give you a perfectly crisp line. In particular, we might find that as we zoom into the potato, we start seeing something like this:

(I’m trying to depict “particles” basically lol.)

The point I want to make is: if this world was non-nebulous, what we would find is that if we kept zooming in on the little circles, we’d eventually get to a place like this:

And zooming in more we’d get:

And eventually we’d end up back at:

While edge of the potato itself did not stay perfectly sharp, the edges of the little balls that it is comprised of do stay perfectly sharp. In a non-nebulous world, as long as you keep zooming in, eventually you’d find a perfectly sharp line that corresponds to the boundary of the original high-level object you were looking at.

Our world is different from this picture I’ve painted in two ways:

- For almost all the lines that you see, when you zoom in to them, they started to become blurry, as in the gradient picture earlier.

- There are some cases where you could argue that zooming close-up will give you the little balls instead, and you might claim that those little balls (the constituent atoms3) actually have definite boundaries. But even if the constituent balls have perfectly sharp boundaries, it is not well-defined which of those balls is part of the original potato and which of them aren’t. It’s a big messy jumble of balls at that zoom level, or as Brian Cantwell Smith calls it, “a stupefying spray of interpenetrating waves of every conceivable frequency.”

Regarding point #2, I recommend this animation for a visualization of how “perfectly definite” balls can generate “nebulous” objects:

there's this cool simulation of "cells" emerging out of simple particles + motion laws

— kasra (@kasratweets) December 1, 2022

what I especially love about it is that it intuitively shows the nebulosity of the "cell": its boundary is fuzzy and it's constantly exchanging particles with its environment pic.twitter.com/uMMLw4stxF

Also see my other post where I provided intuitions about nebulosity by looking at everyday objects with a hand-held microscope.

Is a non-nebulous world possible?

Something I will add is that I haven’t drawn out all the implications of what the world would be like if it was indeed non-nebulous—our everyday world might look completely different if all objects/categories were perfectly well-defined. It might even be the case that our everyday world as it exists would be completely impossible if the SVG-esque property described above was true of reality. My exploration was instead motivated by the question: taking the everyday world as it is, what would we have to see when we look at objects up-close to convince us that “objects are nebulous” is not true?

-

Of note: while zooming in gives us more information about the object, it’s ultimately up to us how to make sense of that additional information – i.e. how to “add up”/aggregate those individual slices we took. I wouldn’t go as far as saying that properties which are invisible at the zoomed-in scale – e.g. the texture of the leather on the chair – just don’t exist. It’s not that the zoomed-in scale is the only true perspective on the chair/cloud; it’s that it is a more information-dense perspective than a zoomed-out view. ↩︎

-

In this discussion I assume that the notion of “zooming in infinitely” is logically coherent and physically possible; I think the former is true, while the latter seems quite obviously false. For the purpose of this discussion, I am claiming that in a non-nebulous world, we would find that at the smallest zoom level that is physically achievable, the boundary would still be perfectly sharp. ↩︎

-

I don’t think even atoms have perfectly sharp boundaries but I’m not sure; please distrust anything I have to say about atoms. ↩︎