This is the thirteenth post in my series of daily posts for the month of April. To get the best of my writing in your inbox, subscribe to my Substack.

The kind of writing I enjoy doing most is something I call a “braindump”, where I write a stream of consciousness on whatever ideas call to me at the moment: insights, readings, questions, struggles, and so on. I find such sessions deeply clarifying and fulfilling, often generating new insights or connections I hadn’t thought of between disparate ideas. I usually don’t publish such thoughts because the lack of a single topic or coherent narrative makes it harder to consume for the reader. But I thought for today’s piece I’d share an example of such a session, to share with you a small slice of my mind.

I made some light edits for clarity, but otherwise kept the original structure of the notes preserved.

- first of all, these days the good moments are really good. I feel like my life is in a state of flow, I feel a strong sense of purpose in what I’m doing, I feel lots of love from the world and people around me. as always though, there are “bad” moments of frustration as well. the smallest things can tick me off, and I sometimes feel a strong need for validation or stimulation.

- I think this is very much a reasonable state of affairs. maybe we could use a bit more silence—a bit more spiritual clarity, really—and a bit more connection with close friends. I was feeling some of this clarity earlier today as I was reading maybe you should talk to someone, and she was talking about her patient julie, and how julie is dying of cancer and how hard that is for her and her husband and just the manifold complexities of the situation.

- “manifold complexities” reminds me, that I recently made the connection between my interest in music/rap, and my interest in writing. there really is a rhythmicity to writing. good writing has a rhythm to it. and your own subconscious mind is fantastically good at generating rhythm, and so if you want good rhythm, the best thing you can do is write just as you think. very rarely do we improve the rhythm by adding edits retrospectively. (it sometimes does happen, but again it’s rare.) instead the rhythm should come from the subconscious generation of the words themselves.

- there’s also a semantic rhythm to writing. or maybe a better way to put it is, a “storyline” to a piece. I keep thinking about Brandon Sanderson’s ideas about “progress, promise, and payoff”. an essay is a journey from one place to another. with each word that I tell you, there’s a whole map of expectations and meanings and emotions in your own mind. a good essay builds up to something. a good story also builds up to something.

- I feel a need to note, however, that life itself doesn’t necessarily take the shape of a good story. life just does its thing. there is no clear sense of buildup, no progress / promise / payoff. however. often, life does serve us an interesting, meaningful, and moving set of events. often it gives us a really great story! the blessing is that we can view the brute facts of life under the lens of a number of different stories, some better than others. so just as we make fictional stories, we also make stories out of our lives.

- and perhaps there is an overarching good story to this universe too. a story that starts with an explosion, and involves the slow coagulation of more and more complex and interesting entities. protons to atoms to complex molecules. meteors to planets to solar systems. (I’m sure I’m getting the order wrong lol.) stars and nebulae. self-replicating molecules, nuclei, cells, organisms, mammals, humans, each stage of the story coexisting with all the previous stages. all the small things are still around, with their own little semi-independent but semi-dependent existence, just as the big emergent things have a semi-dependent existence. individual intelligence, to collective intelligence. growth of technological prowess, growth of scientific knowledge, growth of creative expressive power. these are all pretty good stories too.

- I’ve been reading Kandel’s Principles of Neural Science, and boy is it a good textbook. it’s interesting to make the contrast between his textbook and Bear’s. I think Bear was a good intro—parts of what I’ve read in Kandel so far (specifically the section on neurons and action potentials) would have been a lot harder to read had I not read Bear beforehand. but also, Kandel’s treatment feels more rigorous, and more rich. he really gets into the history and the arguments, which is something I’ve been very interested in.

- for example, something I’ve long wondered is what leads us to believe that action potentials are indeed the information process mechanism of the brain. like ok, nerve cells seem to have this property of quickly changing the potential gradient on their membrane and propagating this change down their axon, but how do we know this isn’t just like, random electrical jittering? and how do we know that all brain cells do it, and so on?

- Kandel actually sheds some light here. he mentions how this guy—Edgar Adrian—actually looked at a bunch of nerve cells in different places in the central and peripheral nervous system and found that they all generate action potentials. and also that action potentials are highly stereotyped—as in, across different cells, they have the same shape. and regardless of the type of input the nervous system receives, the end result is the same: the sensory information is tranformed into an action potential. (and at the other end of the stimulus-response track we have motor neurons that also ultimately output an action potential.) I’m just now remembering, this is pretty much the point I made in my blog post that I wrote at the end of reading the Bear textbook. this stereotyped nature of the action potential is one of the reasons we believe that action potentials are the information transmission mechanism of the brain.

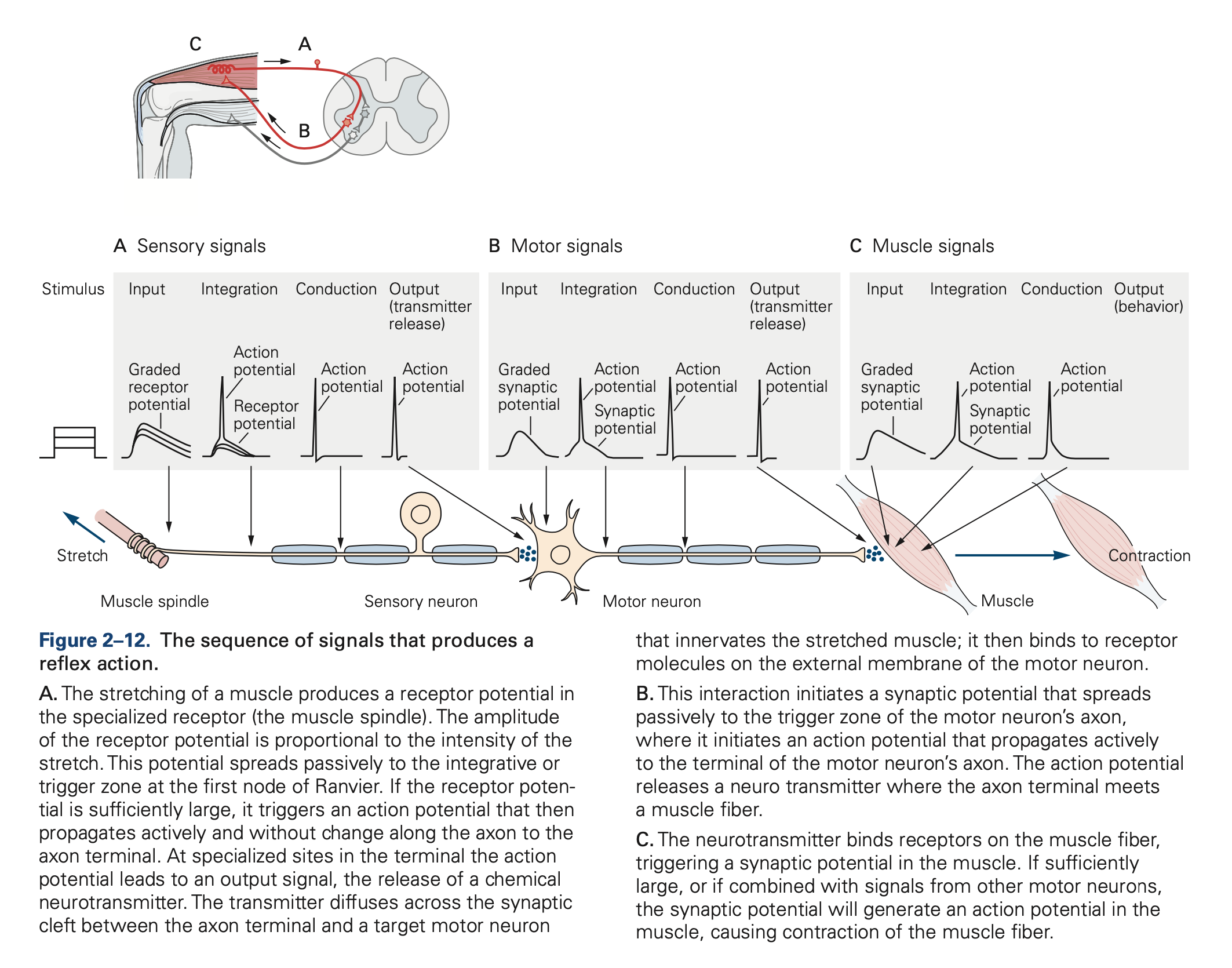

- Kandel also makes a very interesting breakdown of the various sections of the typical neuron: input, signal aggregation, signal conduction, and output. and he shows in this really neat diagram how, at the input stage, the information is graded, i.e. the level of excitation (or inhibition) is on a continuum. but at the aggregation section of the neuron (typically the first “node of ranvier”, or just, the very beginning of the axon maybe?), that graded signal turns into a binary, all-or-nothing signal—the action potential. all action potentials have the exact same amplitude—isn’t that kind of insane? now, action potentials are all-or-nothing, and they have a constant amplitude, but they are able to transmit intensity information by frequency: the faster the action potentials are firing, the more intense the signal is. at the other end of this system you have the output of the neuron, which is, again, a graded signal—the strength of the signal is on a continuum. the strength is just encoded in the amount of neurotransmitter that gets released at the synapse. what an unbelievably strange but interesting information processing system! I don’t know the details of computers / processors / circuits / wires that well, but I’m pretty sure this is a wildly different system from that. and what are the evolutionary histories we can look at to help us understand this signalling system better, i.e. understand why in the world it ended up like this?

Diagram of the components of each neuron in a simple sensory-motor pathway.

Diagram of the components of each neuron in a simple sensory-motor pathway. - what synapses remind me of is olfaction. chemicals released, and then chemicals “sensed” by the ion channels / receptors on the adjacent cell. this is a pretty straightforward, universal-seeming paradigm for transmitting “information” from one cell to another, so I imagine that’s how synapses began in evolutionary history? as for the action potential and the electrical signalling and the baseline imbalance of charge across the membrane surface – I have literally no idea where that might’ve come from lmao.

- I remember looking at a picture of the evolutionary history of the eye (from Cognition and the Visual Arts)—how it began as a literal hole inside which there was photoreceptors, and how over time the skin around that hole kinda curved inward, to form an “optical pocket” (maybe that’s an actual term), and then eventually that pocket evolved more and more into a literal sphere, and that’s where the eye came from. and it makes sense, because I think that the formation of the sphere makes vision a lot easier, ah yes of course – because it restricts the amount of light coming in to a very narrow hole, and it allows that light to then disperse pretty widely onto the retina at the back, which I think allows us to distinguish the potential objects that are the sources of the light, quite well. I mean it makes a lot of sense—imagine a ton of rays from a bunch of different angles and places—if you don’t have a small hole to only get a small number of the rays, you’re gonna get a lot of interference. (or something – I’m not totally able to visualize it rn.) but this all accords with the intuitive fact that if you make a tiny eyehole with your hand, in front of your bad eye, you’ll actually get a very clear image! wow.

- my conversation with R Sal Reyes was a really good reminder of how interesting and useful it can be to look at evolutionary history if you want to understand things like the brain. he made the great (and obvious) point that the brain, at any point in evolutionary history, was deeply constrained by the machinery it already had. it couldn’t build a whole new brain section out of nowhere—the only modification mechanism it had was random variation of the genes lol. ok just re-acknowledging how insane that is. the brain of monkeys evolved into our brain by virtue of random genes changing lol. this world is stranger than fiction, truly!!! but yes, the convo with Sal was a good reminder of this, and I’m very intrigued to fully read through his stuff about consciousness and memory, he really does seem to have a coherent, unified and intuitively satisfying theory of the mind and brain.

- I generally avoid being arrogant about anything but I’ve been thinking about how you do need some kind of arrogance in some places – it’s a good function that pushes you to do things! I’m reminded of the documentary about Robert Caro and Robert Gottlieb, in which Gottlieb—Caro’s editor—was like, “I’m the best reader in the world”. and he said something like “I have a ton of self-doubt in almost all my other abilities, but this is the one area I don’t have self-doubt.” and I was like, wow, ok that’s pretty sick. here’s a man with humility, but a healthy smidge of unbridled confidence in a specific domain. and I want to allow myself to have that kind of arrogance in specific domains, regardless of whether it’s actually warranted or not!!!! and that’s the key, being willing to be blindly arrogant in specific circumstances, without the need for reassurance (in fact perhaps arrogance is literally just the mindstate where you need absolutely no reassurance.) not needing reassurance is incredibly powerful.

- in an essay I might publish soon, that would be about “the curse of knowledge”, something I want to say is: the number one thing to protect yourself from the curse of knowledge is to cultivate the ability to let go of attachments. it’s as simple as that. sure you can put a limit on how much you read, but in general reading more is very beneficial, and you can have the benefits of reading without the drawbacks of being “blinded” by a conceptual paradigm if you maintain your access to beginner’s mind. again, we have the John Dewey quote about Alexander Technique, where he pointed out that AT helped with his posture but also helped him take philosophical positions more lightly and switch between them more effortlessly lol. it’s the same mental mechanism!!