This is an outgrowth of A first pass at David Chapman’s metarationality.

In Abstract Reasoning as Emergent from Concrete Activity, David Chapman quotes a summary article about the “E-approaches” in the cognitive sciences:

E-approaches propose that cognition depends on embodied engagements in the world. They rethink the alternative, ‘sandwich’ view of cognition as something pure that can be logically isolated from non-neural activity. Traditionally, cognition is imagined to occur wholly within the brain. It occurs tidily in-between perceptual inputs and behavioral outputs. Cognition is informed by, and shapes, non-neural bodily engagements, but cognition and embodied interactions never mix.

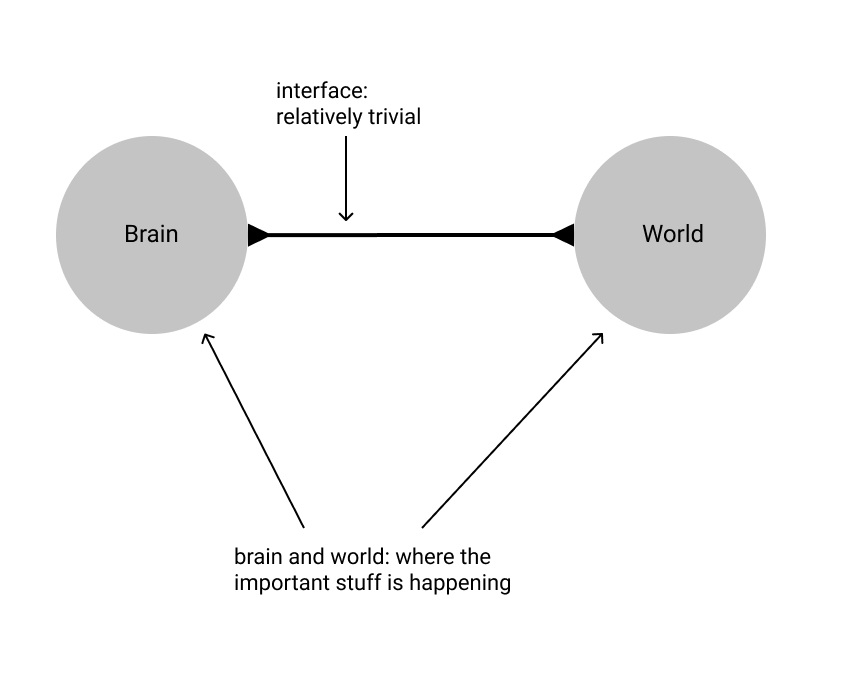

This points to a tangible disagreement with physicist David Deutsch. In The Fabric of Reality, Deutsch argues that there is a clear boundary between our minds and the world, that there is such a thing as “pure” cognition that can be disentangled from the world it’s contained in, and that the interface connecting the world and the mind is comparatively “trivial”.

Trivial in this case means that there’s a finite set of problems we need to solve to perfectly control this interface; not that the solving the interface is easy, but that it’s solvable in finite time, and that the harder problem is in the brain and the world, rather than in the connection between them.

Deutsch argues that we will have solved the interface between our minds and the world once we’ve figured out how to artificially generate nerve signals to a degree of accuracy beyond the brain’s ability to discern:

Once we can artificially generate nerve signals accurately enough for the brain not to be able to perceive the difference between those signals and the ones that our sense organs would send, increasing the accuracy of this technique will no longer be relevant. At that point the technology will have come of age, and the challenge for further improvement will be not how to render given sensations, but which sensations to render. (109)

The problem is: it could be that the notion of “accuracy beyond the brain’s discernibility” isn’t a firm boundary—that as the brain gets more fine-grained signals, it gets better at discriminating them.

Deutsch:

when we look beyond transient technological limitations, we see that image generators merely provide the interface – the ‘connecting cable’ – between the user and the true virtual-reality generator, which is the computer. For it is entirely within the computer that the specified environment is simulated. It is the computer that provides the complex and autonomous ‘kicking back’ that justifies the word ‘reality’ in ‘virtual reality’. The connecting cable contributes nothing to the user’s perceived environment, being from the user’s point of view ’transparent’, just as we naturally do not perceive our own nerves as being part of our environment. Thus virtual-reality generators of the future would be better described as having only one principal component, a computer, together with some trivial peripheral devices. (113)

What environments we shall be able to render will no longer depend on what sensors and image generators we can build, but on what environments we can specify. ‘Specifying’ an environment will mean supplying a program for the computer, which is the heart of the virtual-reality generator. (113)

He does add the caveat:

I do not want to understate the practical problems involved in intercepting all the nerve signals passing into and out of the human brain, and in cracking the various codes involved. But this is a finite set of problems that we shall have to solve once only. After that, the focus of virtual-reality technology will shift once and for all to the computer, to the problem of programming it to render various environments. (113)

I think if it’s indeed true that cognition depends on embodied engagements with the world, then Deutsch’s argument no longer holds up.

It’s been a while since I read this chapter of the book though, so let me know what I’m missing!